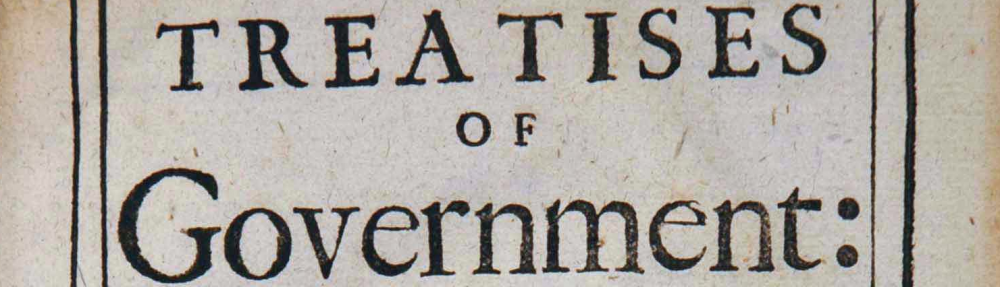

TWO TREATISES OF Government:

In the Former, The False Principles, and Foundation OF Sir ROBERT FILMER, And his FOLLOWERS, ARE Detected and Overthrown.

The Latter is an ESSAY CONCERNING THE True Original, Extent, and End OF Civil Government. LONDON, Printed for Awnsham Churchill, at the Black Swan in Ave-Mary-Lane, By Amen-Corner, 1690.

- Two Treatises of Government. Edited Thomas Hollis. A. Millar, London 1764.

- Two Treatises of Government: A Critical Edition with an Introduction and Apparatus Criticus by Peter Laslett. Cambridge University Press, 1967.

- Two Treatises of Government: Edited with an Introduction and notes by Peter Laslett. Student edition. Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Two Treatises of Government and A Letter Concerning Toleration. Edited and with an Introduction by Ian Shapiro with essays by John Dunn, Ruth W. Grant and Ian Shapiro. Yale University Press, New Haven and London 2003.

- Tutkielma hallitusvallasta. Tutkimus poliittisen vallan alkuperästä, laajuudesta ja tarkoituksesta. Suomennos ja esipuhe Mikko Yrjönsuuri. Gaudeamus 1995

Preface

Book I: The False Principles and Foundation of Sir Robert Filmer, and his followers, are Detected and Overthrown.

II: Of paternal and regal Power

III-VI: Of Adam’s Title to Sovereignty

- III by Creation

- IV: by Donation

- V: by the Subjection of Eve

- VI: by Fatherhood.

VII: Of Fatherhood and Property considered together as Fountains of

Sovereignty

VIII-XI: Of the Conveyance of monarchical Power

- VIII: Of the Conveyance of Adam’s sovereigns monarchical Power

- IX: Of Monarchy by Inheritance from Adam

- X: Of the Heir to Adam’s Monarchical Power.

- XI: Who Heir?

Book II: An Essay Concerning the True Original, Extent and End of Civil Government.

- Second Treatise of Government (Tutkielma hallitusvallasta)

- Tutkielma hallitusvallasta. Tutkimus poliittisen vallan alkuperästä, laajuudesta ja tarkoituksesta. Suomennos ja esipuhe Mikko Yrjönsuuri. Gaudeamus 1995

I: Of Political Power (Poliittisesta vallasta)

- “2. Show the difference betwixt a ruler of a commonwealth, a father of a family, and a captain of a galley.

- “3. Political power, then, I take to be a right of making laws, with penalties of death, and consequently all less penalties for the regulating and preserving of property, and of employing the force of the community in the execution of such laws, and in the defence of the commonwealth from foreign injury, and all this only for the public good.”

II: Of the State of Nature (Luonnontilasta)

- “A state of perfect freedom to order their actions, and dispose of their possessions and persons as they think fit, within the bounds of the law of Nature, without asking leave or depending upon the will of any other man.”

- “A state also of equality, wherein all the power and jurisdiction is reciprocal, no one having more than another.”

- “But though this be a state of liberty, yet it is not a state of licence; though man in that state have an uncontrollable liberty to dispose of his person or possessions, yet he has not liberty to destroy himself, or so much as any creature in his possession, but where some nobler use than its bare preservation calls for it.

- The state of Nature has a law of Nature to govern it, which obliges every one, and reason, which is that law, teaches all mankind who will but consult it, that being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty or possessions; for men being all the workmanship of one omnipotent and infinitely wise Maker; all the servants of one sovereign Master, sent into the world by His order and about His business; they are His property, whose workmanship they are made to last during His, not one another′s pleasure.”

- The execution of the law of nature is, in that state, put into every man’s hands, whereby every one has a right to punish the transgressors of that law to such a degree, as may hinder its violation,”

- All princes and rulers of independent governments all through the world, are in a state of nature.

- Truth and keeping of faith belongs to men, as men, and not as members of society.

III: Of the State of War (Sotatilasta)

- §16 The state of war is a state of enmity and destruction.

- And one may destroy a man who makes war upon him, or has discovered an enmity to his being, for the same reason that he may kill a wolf or a lion; because such men are not under the ties of the common-law of reason, have no other rule, but that of force and violence.

- §17 And hence it is, that he who attempts to get another man into his absolute power, does thereby put himself into a state of war with him; it being to be understood as a declaration of a design upon his life.

- §18. This makes it lawful for a man to kill a thief, who has not in the least hurt him, nor declared and design upon his life, any farther than, by the use of force.

- §19 The state of nature and the state of war, which however some men have confounded, are as far distant, as a state of peace, good will, mutual assistance and preservation, and a state of enmity, malice, violence and mutual destruction, are one from another.

- Want of a common judge with authority, puts all men in a state of nature: force without right, upon a man’s person, makes a state of war, both where there is, and is not, a common judge.

IV: Of Slavery (Orjuudesta)

- §22. Freedom is not what Sir Robert Filmer tells us, a liberty for every one to do what he lists, to live as he pleases, and not to be tied by any laws: but freedom of men under government is, to have a standing rule to live by, common to every one of that society, and made by the legislative power erected in it.

- Having by his fault forfeited his own life by some act that deserves death, he to whom he has forfeited it may, when he has him in his power, delay to take it, and make use of him to his own service; and he does him no injury by it.

- §23. This is the perfect condition of slavery, which is nothing else but the state of war continued between a lawful conqueror and a captive, for if once compact enter between them, and make an agreement for a limited power on the one side, and obedience on the other, the state of war and slavery ceases as long as the compact endures; for, as has been said, no man can by agreement pass over to another that which he hath not in himself- a power over his own life.

V: Of Property (Omaisuudesta)

- §24 Men, being once born, have a right to their preservation, and consequently to meat and drink and such other things as Nature affords for their subsistence

- It is very clear that God, as King David says (Psalm 115. 16), “has given the earth to the children of men,” given it to mankind in common.

- But, this being supposed, it seems to some a very great difficulty how any one should ever come to have a property in anything.

- Nobody has originally a private dominion exclusive of the rest of mankind in any of them, as they are thus in their natural state, yet being given for the use of men, there must of necessity be a means to appropriate them some way or other before they can be of any use

- Though the earth and all inferior creatures be common to all men, yet every man has a “property” in his own “person.” This nobody has any right to but himself.

The “labour” of his body and the “work” of his hands, we may say, are properly his. - Whatsoever, then, he removes out of the state that Nature hath provided and left it in, he hath mixed his labour with it, and joined to it something that is his own, and thereby makes it his property.

- For this “labour” being the unquestionable property of the labourer, no man but he can have a right to what that is once joined to, at least where there is enough, and as good left in common for others.

- As much land as a man tills, plants, improves, cultivates, and can use the product of, so much is his property. He by his labour does, as it were, inclose it from the

common. - §34 God gave the world to men in common; but since he gave it them for their benefit, and the greatest conveniencies of life they were capable to draw from it, it cannot be supposed he meant it should always remain common and uncultivated. He gave it to the use of the industrious and rational, (and labour was to be his title to it;) not to the fancy or covetousness of the quarrelsome and contentious.

- § 36. The measure of property nature has well set by the extent of men’s labour and the conveniencies of life, no man’s labour could subdue, or appropriate all; nor could his enjoyment consume more than a small part.

- § 37 This is certain, that in the beginning, before the desire of having more than man needed had altered the intrinsic value of things,which depends only on their usefulness to the life of man; or had agreed, that a little piece of yellow metal, which would keep without wasting or decay, should be worth a great piece of flesh, or a whole heap of corn.

- §42 Labour makes the far greatest part of the value of things we enjoy in this world: and the ground which produces the materials, is scarce to be reckoned in, as any, or at most, but a very small part of it; so little, that even amongst us, land that is left wholly to nature, that hath no improvement of pasturage, tillage, or planting, is called, as indeed it is, waste; and we shall find the benefit of it amount to little more than nothing.

- This shews how much numbers of men are to be preferred to largeness of dominions; and that the increase of hands, and the right employing of them, is the great art of government:

- 47. And thus came in the use of money, some lasting thing that men might keep without spoiling, and that by mutual consent men would take in exchange for the truly useful, but perishable supports of life.

- 49. Thus in the beginning all the world was America, and more so than that is now; for no such thing as money was any where known. Find out something that hath the use and value of money amongst his neighbours, you shall see the same man will begin presently to enlarge his possessions.

- §50 This partage of things in an inequality of private possessions, men have made practicable out of the bounds of society, and without compact, only by putting a value on gold and silver, and tacitly agreeing in the use of money: for in governments, the laws regulate the right of property, and the possession of land is determined by positive constitution.

- §51 Right and conveniency went together; for as a man had a right to all he could employ his labour upon, so he had no temptation to labour for more than he could make use of. This left no room for controversy about the title, nor for incroachment on the right of others; what portion a man carved to himself, was easily seen; and it was useless, as well as dishonest, to carve himself too much, or take more than he needed.

VI: Of Paternal Power (Isänvallasta)

- §52 Seems so to place the power of parents over their children wholly in the father, as if the mother had no share in it; whereas, if we consult reason or revelation, we shall find, she hath an equal title. This may give one reason to ask, whether this might not be more properly called parental power?

- §54 That all men by nature are equal, I cannot be supposed to understand all sorts of equality: age or virtue may give men a just precedency: excellency of parts and merit may place others above the common level: birth may subject some, and alliance or benefits others, to pay an observance to those to whom nature, gratitude, or other respects, may have made it due: and yet all this consists with the equality, which all men are in, in respect of jurisdiction or dominion one over another; which was the equality I there spoke of, as proper to the business in hand, being that equal right, that every man hath, to his natural freedom, without being subjected to the will or authority of any other man.

- §57 The end of law is not to abolish or restrain, but to preserve and enlarge freedom: for in all the states of created beings capable of laws, where there is no law, there is no freedom: for liberty is, to be free from restraint and violence from others; which cannot be, where there is no law:

- §57 Freedom is not, as we are told, a liberty for every man to do what he lists: (for who could be free, when every other man’s humour might domineer over him?) but a liberty to dispose, and order as he lists, his person, actions, possessions, and his whole property, within the allowance of those laws under which he is, and therein not to be subject to the arbitrary will of another, but freely follow his own.

- § 58 The power, that parents have over their children, arises from that duty which is incumbent on them, to take care of their off-spring, during the imperfect state of childhood. To inform the mind, and govern the actions of their yet ignorant non-age, till reason shall take its place, and ease them of that trouble.

- §59 If such a state of reason, such an age of discretion made him free, the same shall make his son free too. When he comes to the estate that made his father a freeman, the son is a freeman too.

- § 61. Thus we are born free, as we are born rational.

- § 63. The freedom then of man, and liberty of acting according to his own will, is grounded on his having reason, which is able to instruct him in that law he is to govern himself by, and make him know how far he is left to the freedom of his own will.

VII: Of Political or Civil Society (Poliittisesta eli kansalaisyhteiskunnasta)

- §77. GOD, having made man such a creature that, in His own judgment, it was not good for him to be alone, put him under strong obligations of necessity, convenience, and inclination, to drive him into society, as well as fitted him with understanding and language to continue and enjoy it.

- §77. The first society was between man and wife, which gave beginning to that between parents and children, to which, in time, that between master and servant came to be added.

- § 78. Conjugal society is made by a voluntary compact between man and woman, and though it consist chiefly in such a communion and right in one another’s bodies as is necessary to its chief end, procreation.

- § 85. Master and servant are names as old as history, but given to those of far different condition; for a freeman makes himself a servant to another, by selling him, for a certain time, the service he undertakes to do, in exchange for wages he is to receive: and though this commonly puts him into the family of his master, and under the ordinary discipline thereof; yet it gives the master but a temporary power over him, and no greater than what is contained in the contract between them. But there is another sort of servants, which by a peculiar name we call slaves, who being captives taken in a just war, are by the right of nature subjected to the absolute dominion and arbitrary power of their masters. These men having, as I say, forfeited their lives, and with it their liberties, and lost their estates; and being in the state of slavery, not capable of any property, cannot in that state be considered as any part of civil society; the chief end whereof is the preservation of property.

- §94. No man in civil society can be exempted from the laws of it: for if any man may do what he thinks fit, and there be no appeal on earth, for redress or security against any harm he shall do; I ask, whether he be not perfectly still in the [279] state of nature, and so can be no part or member of that civil society; unless any one will say, the state of nature and civil society are one and the same thing, which I have never yet found any one so great a patron of anarchy as to affirm.

- § 89. Where-ever therefore any number of men are so united into one society, as to quit every one his executive power of the law of nature, and to resign it to the public, there and there only is a political, or civil society. And this is done, where-ever any number of men, in the state of nature, enter into society to make one people, one body politic, under one supreme government; or else when any one joins himself to, and incorporates with any government already made: for hereby he authorizes the society, or which is all one, the legislative thereof, to make laws for him, as the public good of the society shall require; to the execution whereof, his own assistance (as to his own decrees) is due.

- § 90. Hence it is evident, that absolute monarchy, which by some men is counted the only government in the world, is indeed inconsistent with civil society, and so can be no form of civil-government at all.

- § 93 Betwixt subject and subject, they will grant, there must be measures, laws and judges, for their mutual peace and security: but as for the ruler, he ought to be absolute, and is above all such circumstances; because he has power to do more hurt and wrong, it is right when he does it… This is to think, that men are so foolish, that they take care to avoid what mischiefs may be done them by pole-cats, or foxes; but are content, nay, think it safety, to be devoured by lions.

VIII: Of the Beginning of Political Societies (Poliittisten yhteisöjen alkuperästä)

- § 96. For when any number of men have, by the consent of every individual, made a community, they have thereby made that community one body, with a power to act as one body, which is only by the will and determination of the majority:

- § 97. And thus every man, by consenting with others to make one body politic under one government, puts himself under an obligation, to every one of that society, to submit to the determination of the majority, and to be concluded by it; or else this original compact, whereby he with others incorporates into one society, would signify nothing, and be no compact, if he be left free, and under no other ties than he was in before in the state of nature.

- §98 Such a constitution as this would make the mighty Leviathan of a shorter duration, than the feeblest creatures, and not let it outlast the day it was born in: which cannot be supposed, till we can think, that rational creatures should desire and constitute societies only to be dissolved: for where the majority cannot conclude the rest, there they cannot act as one body, and consequently will be immediately dissolved again.

IX: Of the Ends of Political Society and Government (Poliittisen yhteiskunnan ja hallinnon päämääristä)

- §123. That though in the state of Nature he hath such a right [property], yet the enjoyment of it is very uncertain and constantly exposed to the invasion of others; for all being kings as much as he, every man his equal, and the greater part no strict observers of equity and justice, the enjoyment of the property he has in this state is very unsafe, very insecure. This makes him willing to quit this condition which, however free, is full of fears and continual dangers; and it is not without reason that he seeks out and is willing to join in society with others who are already united, or have a mind to unite for the mutual preservation of their lives, liberties and estates, which I call by the general name- property.

- § 124. The great and chief end, therefore, of men uniting into commonwealths, and putting themselves under government, is the preservation of their property; to which in the state of Nature there are many things wanting.”

- “Suurin ja pääasiallinen en tarkoitus liityttäessä valtioksi ja asetuttaessa hallittavaksi on siis omaisuuden suojelu, joka on luonnontilassa monessa suhteessa puutteellista.”

- Firstly, there wants an established, settled, known law, received and allowed by common consent to be the standard of right and wrong, and the common measure to decide all controversies between them. For though the law of Nature be plain and intelligible to all rational creatures, yet men, being biased by their interest, as well as ignorant for want of study of it, are not apt to allow of it as a law binding to them in the application of it to their particular cases.

- § 125. Secondly, In the state of nature there wants a known and indifferent judge, with authority to determine all differences according to the established law: for every one in that state being both judge and executioner of the law of nature, men being partial to themselves, passion and revenge is very apt to carry them too far, and with too much heat, in their own cases; as well as negligence, and unconcernedness, to make them too remiss in other men’s.

- § 126 Thirdly, In the state of nature there often wants power to back and support the sentence when right,and to give it due execution. They who by any injustice offended, will seldom fail, where they are able, by force to make good their injustice; such resistance many times makes the punishment dangerous, and frequently destructive, to those who attempt it.

- §130 He is to part also with as much of his natural liberty, in providing for himself, as the good, prosperity, and safety of the society shall require; which is not only necessary, but just, since the other members of the society do the like.

- § 131. But though men, when they enter into society, give up the equality, liberty, and executive power they had in the state of nature, into the hands of the society, to be so far disposed of by the legislative, as the good of the society shall require; yet it being only with an intention in every one the better to preserve himself, his liberty and property; (for no rational creature can be supposed to change his condition with an intention to be worse) the power of the society, or legislative constituted by them, can never be supposed to extend farther, than the common good; but is obliged to secure every one’s property, by providing against those three defects above mentioned, that made the state of nature so

X: Of the Forms of a Commonwealth (Valtiomuodoista)

- § 132. The majority having, as has been showed, upon men’s first uniting into society, the whole power of the community naturally in them, may employ all that power in making laws for the community from time to time, and executing those laws by officers of their own appointing, and then the form of the government is a perfect democracy; or else may put the power of making laws into the hands of a few select men, and their heirs or successors, and then it is an oligarchy; or else into the hands of one man, and then it is a monarchy; if to him and his heirs, it is a hereditary monarchy; if to him only for life, but upon his death the power only of nominating a successor, to return to them, an elective monarchy. And so accordingly of these make compounded and mixed forms of government, as they think good.

- § 133. By Common-wealth I must be understood all along to mean, not a Democracy, or any Form of Government, but any Independent Community which the Latines signified by the word Civitas, to which the word which best answers in our language is Common-wealth,

XI: Of the Extent of the Legislative Power (Lainsäädäntövallan laajuudesta)

- §134 THE great end of Mens entering into Society, being the enjoyment of their Properties in Peace and Safety, and the great instrument and means of that being the Laws establish’d in that society, the first and fundamental positive Law of all Common-wealths, is the establishing of the legislative power, as the first and fundamental natural Law which is to govern even the Legislative. Itself is the preservation of the society and (as far as will consist with the public good) of every person in it.

- This Legislative is not only the supreme power of the Common-wealth, but sacred and unalterable in the hands where the Community have once placed it.

- § 142. These are the bounds which the trust, that is put in them by the society, and the law of God and nature, have set to the legislative power of every common-wealth, in all forms of government.

- They are to govern by promulgated established laws, not to be varied in particular cases, but to have one rule for rich and poor, for the favourite at court, and the country man at plough.

- These laws also ought to be designed for no other end ultimately, but the good of the people.

- They must not raise taxes on the property of the people, without the consent of the people, given by themselves, or their deputies. And this properly concerns only such governments where the legislative is always in being, or at least where the people have not reserved any part of the legislative to deputies, to be from time to time chosen by themselves.

- The legislative neither must nor can transfer the power of making laws to any body else, or place it any where, but where the people have.

- §139. Even absolute power, where it is necessary, is not arbitrary by being absolute, but is still limited by that reason, and confined to those ends, which required it in some cases to be absolute, we need look no farther than the common practice of martial discipline: for the preservation of the army, and in it of the whole common-wealth, requires an absolute obedience to the command of every superior officer, and it is justly death to disobey or dispute the most dangerous or unreasonable of them; but yet we see, that neither the serjeant, that could command a soldier to march up to the mouth of a cannon, or stand in a breach, where he is almost sure to perish, can command that soldier to give him one penny of his money; nor the general, that can condemn him to death for deserting his post, or for not obeying the most desperate orders, can yet, with all his absolute power of life and death, dispose of one farthing of that soldier’s estate, or seize one jot of his goods; whom yet he can command any thing, and hang for the least disobedience; because such a blind obedience is necessary to that end, for which the commander has his power, viz. the preservation of the rest; but the disposing of his goods has nothing to do with it.

- § 140. It is true, governments cannot be supported without great charge, and it is fit every one who enjoys his share of the protection, should pay out of his estate his proportion for the maintenance of it. But still it must be with his own consent, i. e. the consent of the majority, giving it either by themselves, or their representatives chosen by them.

XII: The Legislative, Executive, and Federative Power of the Commonwealth (Valtion lainsäädännöllisestä, toimeenpanevasta ja kokoavasta vallasta)

XIII: Of the Subordination of the Powers of the Commonwealth (Valtion eri valtojen alisteneisuudesta)

XIV: Of Prerogative (Erivapaudesta)

- Many things there are, which the law can by no means provide for ; and those must necessarily be left to the discretion of him that has the executive power in his hands, to be ordered by him as the public good and advantage shall require

- On monenlaisia asioita, joista laki ei millään voi huolehtia, vaan ne on välttämättä jätettävä toimenpanovaltaa käyttävän harkintaan. Hän antaa määräykset yleisen hyvän ja edun mukaisesti.

- This power to act according to discretion for the public good, without the prescription of the law, and sometimes even against it, is that which is called prerogative :

- Erivapaudeksi kutsutaan valtaa toimia yleisen hyvän parhaaksi harkintavallalla ilman lain määräystä ja joskus jopa sitä vastaan.

XV: Of Paternal, Political and Despotical Power, Considered Together (Yhteinen tarkastelu isänvallasta, poliittisesta vallasta ja despoottisesta vallasta)

XVI : Of Conquest (Valloittamisesta)

XVII: Of Usurpation (Vallankaappauksesta)

XVIII Of Tyranny (Tyranniasta)

- “Tyranny is the exercise of power beyond right, which nobody can have a right to. And this is making use of the power any one has in his hands, not for the good of those who are under it, but for his own private, separate advantage.—When the governor, however entitled, makes not the law, but his will, the rule ; and his commands and actions are not directed to the preservation of the properties of his people, but the satisfaction of his own ambition, revenge, covetousness, or any other irregular passion.”

- “Wherever the power, that is put in any hands for the government of the people, and the preservation of their properties, is applied to other ends, and made use of to impoverish, harass, or subdue them to the arbitrary and irregular commands of those that have it ; there it presently becomes tyranny, whether those that thus use it are one or many.”

XIX Of the Dissolution of Government (Hallinnon hajoamisesta)

- “But if they [people] have set limits to the duration of their legislative, and made this supreme power in any person or assembly only temporary; or else when, by the miscarriages of those in authority, it is forfeited; upon the forfeiture of their rulers, or at the determination of the time set, it [supreme power] reverts to the society, and the people have a right to act as supreme, and continue the legislative in themselves or place it in a new form, or new hands, as they think good.